It’s Not a Small World After All

Published onBy Pico Iyer

Stepping off a United Airlines plane in San Francisco, 18 months ago, I was greeted by the slogan, “The word ‘foreign’ is losing its meaning.” I got out two flights later, in Mashhad, Iran, and was greeted by an air-bridge lined with portraits of “martyrs” from the Iran-Iraq War.

That tiny contrast might have been a reminder of how treacherous it is to assume that the word “foreign” is losing its meaning. Indeed, the distances, the differences between cultures are often greater than ever before, in part because of the illusion of closeness. Multinationals have every investment, quite literally, in telling us that we’re all part of a single market, and idealists may hopefully echo them; my experience, after 39 years of travelling the globe, almost without a break, suggests the opposite.

Yes, we may share the same fast-food joints and Seattle coffee-houses, perhaps. Yet I defy anyone to go to a McDonald’s outlet in New Delhi (full of commotion and the smell of spiced chai, with mostly vegetarian dishes on the menu) and tell me that it’s any less Indian – or any more like a McDonald’s in Toronto – than many an Indian restaurant nearby. Or go into the McDonald’s down the street from me in Nara, Japan: Are the “Moon-Viewing Burgers” that you see on the menu to be found in Santa Monica, Calif.? Are the chic girls in Dior and Saint Laurent akin to your neighbours at the next table in Halifax? Is the way they speak – or don’t speak – and cover their mouths when they smile any less Japanese than it would have been five centuries ago?

Yes, we may share the same cultural products. But go to a showing ofAvatar in China, and tell me that it carries the same meaning for its audience as it would in Studio City. For the former, I’m sure, it’s as much about environmental destruction as to the latter it might be about a dazzling new technology. Watch the same movie in Baghdad and it becomes a parable about imperialism. Every country may draw from the same pop-cultural pool, but each translates it into its own context and language and tradition. We file into the same movie, but come out having seen a radically different film.

Again and again, in fact, what strikes me when I touch down in Jerusalem or Pyongyang is not how much it shares with Washington or London, but how much it doesn’t, in spite of common surfaces, (yes, nine months ago, I did see the two pizzerias and the 36-lane bowling-alley in North Korea’s capital). Which is why travel is more urgent than ever: Our screens vividly bring faraway places into our homes, projecting an image of closeness, but every encounter with the foreign in the flesh reminds us forcibly of how much lies far beyond our reckoning.

Thus political differences have hardly diminished, I would say, even as we all join in on Let it Go and hurry to American Sniper. Go to the West Bank, and most of the kids you see may be wearing T-shirts and jeans; I doubt anyone would say that they’re any closer to their counterparts in New York (or Tel Aviv) because of that. The more we may know what Arabia looks like, from movies such as Syriana, the more those in the Gulf may watch American Idol, the less we may know about what the Other really thinks deep down.

It’s almost as if the 21st century and the first century are living side by side, nowadays, but also back to back, across the globe and in your own province. Many a Torontonian surely feels that rural Ontario may be a far more foreign country than is New York or even Hong Kong; even in our major cities the gap between rich and poor is increasing daily. Someone from Santa Monica is far more likely to find herself in Shanghai or Paris than in the gritty areas around South Central Los Angeles 10 minutes from her home. Even if we’re all on the same page, more and more people are in the margins.

Of course, the gulfs and divisions that remain aren’t entirely a terrible thing. When people say the world is growing homogeneous, losing its savour and individuality, I wonder if they’ve been to Yemen or Ethiopia recently. If someone tells you that we’re all blending into a Disneyland whole, singing “It’s a small, small world,” take them across town to where Haitians and Somalis are struggling to get by. Covering six Olympic Games in 14 years reminded me that the family of man is about as united and harmonious as many another family, even when on its best behaviour.

In Isfahan, Iran, not long ago I found the stores filled with pirated copies of Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs, and last year in North Korea I saw a local crane forward to ask two visiting workers from Apple how Tim Cook’s management style differed from that of his celebrated predecessor. In the mausoleum where Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il lie, embalmed, we saw the sleek MacBook that the latter was said to have been using when he was reportedly felled by a heart attack on a train (our two Appleites confirmed that this was the perfect model to have in 2011, when he died). It’s wonderful that we can share more and more, and enjoy the tastes of foreign cultures in our hometowns and online.

But pity the politician who assumes that will really bring him any closer to Beijing or Tehran. The only way we’ll survive the global neighbourhood is by assuming we know nothing and recalling that a “Yes” in Tokyo – or Mexico City – conveys what we would mean by a “No.” I love the way that we can experience Jamaica, Pakistan, Haiti, Vietnam in our classrooms and cities; I shudder at the notion that to see them is to think we understand them or can easily be one with them.

Some people worry that soon all of us will be speaking English; my deeper fear is that, even if we are, we’ll still be largely incomprehensible to one another.

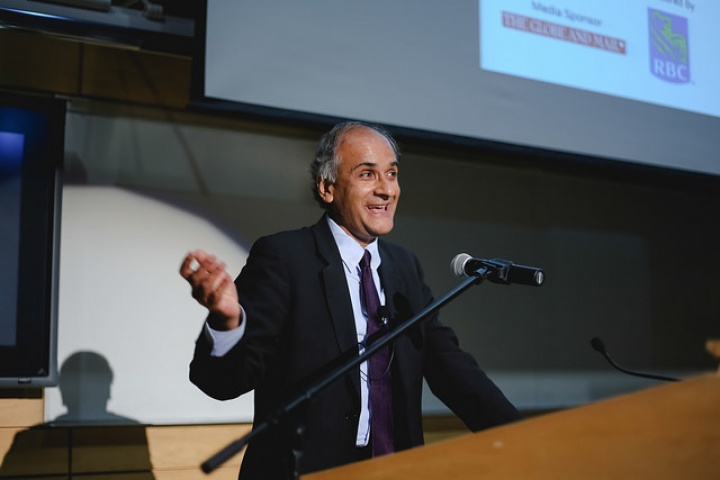

Pico Iyer

Pico Iyer is the author of a dozen books such as The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere and Video Night in Kathmandu, has been writing about his travels, movement and the notions of home for more than 30 years.

On May 7, 2015, Pico Iyer was the the distinguished guest speaker at the inaugural GDX Annual Lecture: Big Ideas on Diversity, Prosperity and Migration.

This article originally appeared in The Globe and Mail on June 6, 2015 and is reprinted with permission.